Blue Sunshine is a microcinema I co-founded in Montreal with my friend Dave Bertrand in June of 2010 and it ran until June 2012 when our two-year lease ran out. The website still exists HERE, though it threatens to become inoperable at any time.

Blue Sunshine is a microcinema I co-founded in Montreal with my friend Dave Bertrand in June of 2010 and it ran until June 2012 when our two-year lease ran out. The website still exists HERE, though it threatens to become inoperable at any time.

It’s a long story, perhaps best told in this essay I wrote for Incite Journal of Experimental Cinema, Vol. 4: The Exhibition Guide, which is now out of print:

BLUE SUNSHINE: THE LIFE AND DEATH OF A MICROCINEMA

Kier-La Janisse

After running a horror film festival in Vancouver (CineMuerte), four years as a programmer for Austin’s Alamo Drafthouse (the closure of the original single-screen downtown venue I programmed for coincided with my rather unceremonious deportation) and a brief stint in a nebulous role at the Winnipeg Film Group’s Cinematheque, I’d been toiling away as an independent exhibitor, four-walling ill-equipped venues, cobbling together ‘atmosphere’ in bars and backyards, and realized I had to take that risky leap to the next level – the ill-advised and oft-dreamt-of ‘permanent venue’ – before I burnt out completely. While the pop-up style of exhibiting has its benefits – less compounded risk, no overhead, the ability to be spontaneous in both vibe and programming – the constant set-up and tear down are physically exhausting and promotion is a nightmare. Audiences don’t understand the concept of an independent exhibitor. They want a regular place that has a regular calendar they can look to on a regular basis, or else they just can’t wrap their heads around what you’re doing. It’s true. People are dumb that way. So like most exhibitors, what I really wanted more than anything was my own movie theatre.

But I was not alone in this endeavor: after much back-and-forth about how wouldn’t-it-be-nice-to-move-to-Montreal-and-open-a-movie-theatre-in-a-city-where-people-still-care, fellow film aficionado David Bertrand, an old acquaintance from Vancouver but hardly a close friend – although he would come to be one of my best friends in the two years that followed – joined me in dropping everything to move to Montreal to open our very own microcinema, which we would name after Jeff Lieberman’s 1978 LSD horror flick, Blue Sunshine. But how do you open a cinema with no startup capital and no prospects for getting any?

Well, if you’re like me, you stop buying food and move money around from something you should be spending it on to something you definitely shouldn’t be spending it on. I put on my first film festival in 1999 with my student loan, and for my part I opened Blue Sunshine with a government grant that was intended for a short film I still haven’t completed (I admit it, I’m an exhibition addict). For his part, Dave had a line of credit he’d built up over a young lifetime of being – dare I say – financially responsible, a concept that was foreign to me. I’m not bad with other people’s money, having managed budgets for several organizations in the past – but with my own money I always go for broke. And broke is where we ended up in no time flat.

After finding a suitable 3rd storey live/work loft on Craigslist and getting it OK’d by the City as being in an approved zone for a cinema provided we could come up with a $300 fee to change its usage from Group D (office) to Group A2 (gallery, cinema etc), we arrived in Montreal on June 1, 2010, signed our lease, got our liability and property insurance, and set about some small renovations to modify the place for our proposed use (including the construction of a second bathroom and a tiny projection booth). The landlady was a nice, if somewhat overmedicated bohemian who revealed to us that our place used to be the apartment of Ivan from Men Without Hats, as well as a holiday apartment she once rented to Robert DeNiro. There was also some connection to the Titanic, but I don’t remember what it was. It was in the heart of St-Laurent boulevard, which we discovered to our dismay was so overrun with drunk students – McGillionaires, as one of our volunteers called them – that most of our intended audience actually avoided the strip altogether, which meant that, centrally located or not, we suddenly had a promotional challenge on our hands. Meanwhile we’d signed on for 2 years at a nearly $3000/mo rent because the place was so central. Over the next two years it would be this rent, as well as the unexpectedly high utility bills (which the previous tenants had sadly lied to us about), that would do us in.

We agreed on a mandate, which was to present classic exploitation side by side with arthouse and experimental cinema and no stratification. We fixed our opening date as Friday June 25th, with the newly-restored Canuxploitation classic Cannibal Girls as our kick-off film. We sent out press releases and updated our new website with the first month’s lineup, which boasted a lot of rare 16mm. Thankfully, the press was very responsive and it looked like we were going to get some major ink. Which would normally be considered a good thing – if it weren’t for the fact that a week before our opening, the City denied us our operating permit.

We met with an old theatre mogul and movie producer who told us in the nicest way possible that we were morons if we planned to open with no permit. So, that’s exactly what we did. With our faces plastered across the film sections of at least three major papers and a few news websites, we opened our doors to local cinephiles – making them fill out membership forms to our “private club” for good measure, though we doubted this actually gave us any legal leg to stand on –and waited for the city to show up and shut us down, hoping we’d make it through at least one film before it happened. But thankfully instead of the cops or the Regie du Cinema, we had 50-odd cinephiles crammed into our little space, laughing and cheering in between craning their necks to see the bottom of the screen which was lower than we’d planned due to a mis-measurement in the ceiling height. We would have many nights like this over the next two years; not as many as we would have liked, but enough to confirm that Montreal audiences cared about us.

Further visits to the City gave us conflicting advice that became a year-long Kafkaesque nightmare involving crooked architects, Napoleonic law, and insurmountable catch-22s. After presenting the city with architect-approved blueprints that detailed the installation of the required fire doors (a $6000 expense), the city came up with a rather Byzantine excuse for denying us the permit. Fire doors open outward. If we put a fire door in the back of the building, it would be opening outward onto our fire escape. The problem was that, according to city blueprints, our building went right up against the edge of its property line, and the fire escape was technically on city property. And you can’t have a door open outward onto city property! He recommended that we knock out the back wall and build an alcove the door could open outwards onto. But of course, we were in a heritage building and we weren’t allowed to knock out exterior walls, even if we could have afforded it, which obviously we couldn’t. I was so furious I was shaking, and Dave had to hold me back from punching the guy. “What am I in a Norman McLaren movie??!! You’re afraid my flower might grow on your side of the fence!!????” (*actual dialogue). He just shrugged his shoulders as we left his office, dejected.

We forged ahead anyway. We screened films three nights a week, with Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies classes for mid-week, and marked out loose ‘themes’ for each night in attempt to build up a loyal audience for those nights – although this demarcation could shift depending on what opportunities popped up. We got everything from filmmakers, distributors or archives, and paid rental fees unless they were waived (which, thankfully, was often). We preferred 16mm film or DVCAM, and had a rule about DVD – we only used it if that was what the filmmaker sent as their exhibition format. In the rare case where we really wanted to present something from a foreign DVD for which there were no prints in circulation, we had to add value to the ticket: free drinks, free food, tactile souvenirs of some sort (an international series of Diabolikal Super Kriminal films from the 60s came with collectible passports). Dave’s taste was slightly more commercial than mine, so the movies he picked tended to attract better audiences, but by ‘more commercial’ that just means he would pick The Seven Ups while I would pick Electraglide in Blue. It was still a thin (blue) line.

The first month alone set the standard for what would come: screenings of La Brune et Moi, The Beaver Trilogy, Rolling Thunder, Devil at Your Heels, Ray Davies’ Return to Waterloo, the made-for-television stunner Diff’rent Strokes: When the Laughter Stopped, Jon Moritsugu’s Terminal USA, British suedehead classic Bronco Bullfrog, and our first sold-out show: Chickenhawk: Men who Love Boys.

First year guests bounced all over the genre map, from Stuart Gordon and Dennis Paoli conducting a class on adapting HP Lovecraft to the screen, Halter presenting his In Search of Sunn…multimedia show on the supernatural/pop-science films of Utah’s Sunn Classic Pictures, Kimmy Robertson came in from LA for an all-night Twin Peaks marathon, rock critic Richie Unterberger came in from SF to present a multimedia show about The Velvet Underground, Canadians Jamie Travis and shock-rocker Corpusse visited, Pittsburgh garage icons The Cynics hosted a Halloween screening of Bad Ronald, director Frank Vitale introduced a rare 16mm print of his queer classic Montreal Main, as part of a launch event for Tom Waugh’s book about the film, iconoclastic musician Raoul Duguay presented his 1972 film Ô: Ou L’Invisible Enfant, and we discovered that Stephen Rosenberg, who played Jacob Two-Two in the 1978 low-budget Montreal production of Jacob Two-Two Meets the Hooded Fang, worked at the hair salon a few doors down. An early coup was getting director Robert Morin to attend a screening of Petit Pow! Pow! Noel, although we were still to green to realize how much of a coup it was, until other fest programmers started asking us how the heck we’d convinced him to come to our hole-in-the-wall joint when he wouldn’t even show up to the Jutra Awards. What can I say, sometimes naivete is your friend!

Meanwhile we were still operating without a permit. After 5 months of the architect stringing us along with no progress whatsoever, we told him we didn’t need his services anymore and he threatened to sue us unless we paid him $3000 for the ‘work’ he’d supposedly been doing. Our income was gutted over the next 5 months as we struggled to pay him off. By February 2011 we were on the verge of closing, and since we couldn’t just walk out of our lease, would have had to declare bankruptcy if some of our regulars hadn’t banded together to put on a couple benefit shows to help us pay off our bills to the useless bloodsucking architect. Our plan was to sublet and get out of there, but all the ‘for rent’ signs along our block didn’t bode well for our ability to rent the place out anytime soon. We were going to have to tough it out, and for the next two years, we scraped by, practically starving, our clothes collecting holes, fighting off creditors – but through it all, we never compromised our programming, and I don’t even think we knew how to. Our pride in what we put on screen, and our “ghetto-pro” presentation standards as well as the handful of trusty volunteers and regulars kept us going.

Year one also saw screenings of 80 Blocks from Tiffany’s, Gainsbourg, L’homme qui aimait les femmes, oddities like Das Shleyerband and Michele O’Marah’s Valley Girl, and a Biker film all-nighter that almost resulted in mass drunken fisticuffs. We also held the first of our annual Black Heritage Month celebrations, which was a bit of a bust, even though we had rare 16mm prints of Cooley High, Sugar Hill, Watermelon Man, Black Like Me, Ben Russell’s Black and White Trypps #4 and documentaries about Nina Simone, Blowfly and Don Letts, but by the second year we were filling out the place for 16mm prints of Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song, Dr. Black and Mr. Hyde and Hickey and Boggs, as well as documentaries on Richard Pryor and the doomed Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis. The place was adorned in artifacts such as original Black panther newspapers, black power paperbacks, posters, a gallery of icons from Stokely Carmichael to Don Letts, and even the Malcolm X boardgame (in which you try to defeat the system at an incredible disadvantage, and based on my own attempts, you actually can’t win). Between Dave and I, we collected all kinds of weird ephemera, and used the screenings as an excuse to show them off.

For our first year anniversary we invited our patron saint, Jeff Lieberman, director of our namesake film, Blue Sunshine. He came on his own dime, and even agreed to stay in our back room, which had a fold-out futon for low-maintenance guests, but somehow managed to go to bed without getting bedding from us and subsequently froze all night. When I woke up the next morning, he was already up, cup of joe in hand, ready to kill me.

Pip Chodorov came in to present his poignant documentary about the history of experimental film, Free Radicals; composer Germain Gauthier and director George Mihalka came in for a rare 16mm screening of Pinball Summer (the Montreal-shot sex romp Mihalka directed before making it big with My Bloody Valentine), and they had such fun that it prompted the re-release of the film’s blissful soft-pop soundtrack (with liner notes by yours truly); animator Leslie Supnet presented a retrospective of her short films and an exhibit of her illustrations, Yan Moore, co-creator of TV’s Degrassi franchise, came in to moderate a scriptwriting workshop and to introduce the infamous Degrassi School’s Out! finale, which almost resulted in two lawsuits. We invited Ron Mlodzik, the star of Cronenberg’s first films Stereo and Crimes of the Future, but he chickened out at the last minute, possibly because he’s now an orthodox priest or maybe because my first email to him contained a marriage proposal.

At some point we realized we would never get a permit and couldn’t afford to spend any more time chasing it. So we just crossed our fingers and hoped we could keep it on the DL until our lease was up in June 2012. Neither of us wanted to be in this situation – we’d planned to open a legitimate business, but without the permit all we had was the expenses of a legit business – commercial rates on rent, utilities, insurance, film rentals and shipping – without the benefit of protection. We could be shut down at any time, or handed a crippling fine that would leave us in debt for the rest of our lives. But if we tried to walk out of our lease, we’d face the same kind of legal action. We were stuck, and both of us hung our heads as we borrowed money from friends and relatives and sold off our possessions to stay afloat.

But aside from the financial burden, we loved everything Blue Sunshine stood for. We loved the people it brought together, the creative alliances we saw forming at screenings, the venue’s built-in blend of professional exhibition space/house party, and the way people in other cities would praise our programming – which can be an important boost when catering to a niche market. We knew we were doing something right, even if we couldn’t sustain it with the current expenses.

As a last ditch attempt to save the place, we applied to the Canada Council for the Arts for $12K in operational assistance. Perhaps it wasn’t fair to put it on them, but we let the Canada Council decide our fate. We sent in our application and waited. Four months later we got a letter stating that they regretfully had to pass on our application, and that was that. By this time, I’d been offered a free place to stay in Scotland for a few months, where I could act out my looming mid-life crisis, and Dave urged me to go, saying he would take care of closing out the last few months of Blue Sunshine. I felt like I was abandoning ship, but my mental health demanded the break. I kept tabs on everything from overseas and offered input when needed, but as the last calendar got printed and the final facebook invitations were sent out, Dave and I started to get emotionally distraught. Suddenly my getaway plan – a beautiful centuries-old farmhouse – started to seem like an obstacle that was keeping me from where I desperately needed to be. And when Scottish friends offered to whisk me away to a remote island in the Hebrides for a week, I realized too late that it coincided with both Blue Sunshine’s last screening and closing party, so I wouldn’t even be able to participate via Skype. I just had to imagine everything I had built falling away without me.

Via Dave’s play-by-play and a pathetic amount of facebook stalking I was able to grasp a full picture of the final events. Our last screening – a 16mm print of meathead classic This is Spinal Tap – was packed to the gills (the one time in two years we allowed the place to get seriously over capacity) and full of teary-eyed regulars who sang along with the film and were stunned into silence by the special guest who phoned in to sing them a rendition of Highway to Hell via Skype – namely Chinese outsider artist WING. It was an inspired move on Dave’s part to get Wing in the house, ‘virtual’ though it may have been. For the closing party a week later, all the chairs were moved out, clearing the way for nearly 12 hours of drunken idiocy (and hangovers that lasted three times as long). With the cops preoccupied with the student riots happening all over downtown Montreal, Blue Sunshine’s sudden status as late-nite booze can was the least of their concerns. As two years worth of Blue Sunshine trailers unfolded onscreen, the band ‘Interracial Love Triangle’ performed, stupid hats were worn, and new colloquialisms were invented. “This place looks like Animal House!” said one of the regulars, surveying the morning-after debris. So much for the damage deposit.

Everyone kept saying it was the end of an era. It was only two years, a blip in the lifespan of your average cinema, but in that two years our cockamamie scheme yielded something palpable. Maybe Blue Sunshine wouldn’t be around anymore, but we’d given people hope, to some extent – hope that when studios and distributors decimate their 35mm prints and abandon film for glitched satellite broadcasts, individuals can create their own clubhouses and secret societies, fuelled by film. And if you have batteries and can develop film by candlelight, then making films is possible even after the apocalypse! And while Blue Sunshine was just one small theatre in the much larger cinematic apocalypse that is pressing down upon us as we speak, we went out like a jerry-rigged battletruck face-first into our inevitable doom. That’s how we roll. As a wise duo of white-soul singers once said: “Hard work means something. Live first, die laughing.”

FURTHER READING:

Blue Sunshine is also a case study in Donna DeVille’s 2014 PhD thesis “The Microcinema Movement and Montreal” which you can read HERE >>

There’s also a great interview Paul Corupe did with us on the Canuxploitation website when we closed HERE >>

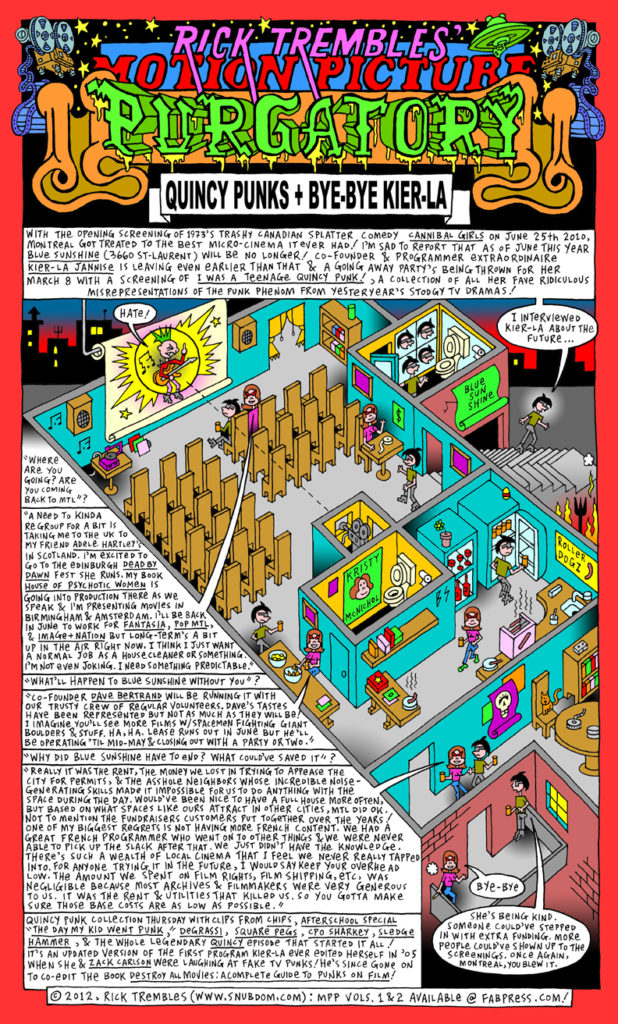

And probably the best surviving record of what Blue Sunshine actually looked like inside is this comic strip by Montreal underground artist Rick Trembles: